Museum Mascots, Yoga and an IMAX Theatre: European Museums for Everyone

When lectures for pensioners, workshops for children and art therapy programmes began to appear on the list of services offered by museums in Kyiv a few years ago, I quickly signed up my grandmother for a lecture and sent out information about children’s activities to those of my friends who have kids.

And when the Maidan protestors pitched their tents in the capital’s centre and it became clear that they were serious and there to stay, my colleague organised cultural visits to museums for the protestors. A few months later, a war broke out, the public sector strained itself in the support of the Ukrainian army – and museums were again left on the sidelines, introducing free admission for ATO participants.

In all these cases, museums carried out the functions of raising awareness and rehabilitation. They began to respond to the demands of society to be a platform for live communication.

But when I recently had to pull a buggy to the top of the steps of the National Art Museum, I realised that even our most advanced institutions do not meet the requirements for equal access for the various sections of the population.

It is the norm in today’s world to have wheelchairs available at the entrance, general information printed in braille, tactile models present at exhibitions, and families with children (this is often one of the largest target groups) receive special educational programmes.

Museums around the world have for decades been trying to meet the demands of society and, at the same time, even successfully competing with private business in the tourism sector.

HELSINKI, FINLAND

Today, the central art museum of the country, Ateneum, is quite friendly to the various visitors of the institution.

This grandiose building from the late 19th century can be easily accessed by lift. The lift also works inside the museum; here you can rent wheelchairs, baby buggies, canes and magnifying glasses. And guide dogs are very welcome too.

|

|

Ateneum, the art museum of Finland, opened its doors to visitors in 1888. Photo: Alvesgaspar |

The museum offers, besides the usual guided tours, programmes for schoolchildren, tours in sign language, services for people with impaired vision and hearing, the possibility to modify master classes for visitors with special needs.

Scanning all this information on Ateneum’s website, it is hard to believe that in the 1980s there were calls in Finnish society to close down the museum or even raze it to the ground due to professional incompetence.

In Finland, criticism of art museums for being “stuck in the past” and not having “clear social functions” appeared in the 1950s. At the time, as a result of social change, the capital’s population has doubled and new residents from rural areas were until recently populating areas that did not belong to the city.

Critics pointed out that despite the significant growth in the capital’s population this did not provide positive dynamics to museum visits. Thus, the Ateneum national gallery received 35,000 visitors in 1925 and 30 years later it only had 34,000.

The changes came during the overhaul of Ateneum between 1984 and 1991. “It was decided that the museum should become a public space, not push people away but bring them in,” says Erica Othman, educational curator.

According to her, the new trends were borrowed from the experience of Swedish museums. For example, children’s programmes were – in line with public demand – offered back in the 1970s.

To this day, Ateneum is looking for its own ways of communicating with visitors and attracting them into the museum’s life.

|

|

The “Christmas Card” seminar at Ateneum, December 2015. Photo: Ateneum |

For example, a museum audio guide was developed for the exhibition dedicated to the famous Finnish composer Jan Sibelius. There are workshops for various age groups (from 3) and for the use of different techniques (silkscreen printing, pottery, drawing), during which discussions of the role and development of art are encouraged.

A few years ago, Ateneum introduced the “art menu” programme. It was developed in collaboration with a network of restaurants: by ordering such a menu, the gourmet gets a ticket to a museum exhibition.

“A special menu was developed for each exhibition – be it the exhibition dedicated to Sibelius or the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson,” explains Erica.

Another institution of the Finnish National Gallery, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, is also trying to meet the demands of the public and, simultaneously, actively guide it.

Opened in 1998 Kiasma, on the basis of lots of criteria, comes under the definition of a contemporary museum. Here you will find full inclusion and accessibility. There are no stairs at the entrance, all floors can be accessed by lift, if needed you can rent chairs and walkers with wheels, flashlights or magnifying glasses.

|

|

Baby buggies that can be rented at Kiasma. Photo: Svitlana Menchinska |

The museum has separate toilets designed for people with special needs. In addition, dogs are allowed when they are assisting people with vision or hearing impairment.

Other services for people with vision impairment include guides and museum staff, raised-relief maps of the museum and a braille plan, and the opportunity to learn about certain exhibits through touch.

Like in other developed museums, a splendid shop operates here too (books, souvenirs, art objects) in addition to a restaurant currently offering set lunches. This is just one more way of attracting visitors, and souvenirs, although small, are a good way to remind visitors of the museum and stay in touch.

According to Kiasma, the primary role of the institution is “to educate the public on contemporary art and to strengthen the status of art in Finland in general”. Therefore, the museum offers up to ten different workshops and guided tours: from short activities for infants and their parents to workshops for therapeutic and rehabilitation groups.

In addition, there is a theatre at Kiasma. To help the audience enter the world of contemporary performance, a special service was created here called the “escort service”, which is to see a play in the company of a professional actor.

A library of contemporary art from the 1960s to the present day is also responsible for the purpose of education. Any visitor to the museum has access to the library.

When examining the educational programmes of Scandinavian museums, I noted a trend: many of them have a certain museum friend for children, a funny mascot character who accompanies small visitors during their museum visit and talks about the exhibition in a game form.

At Kiasma it’s the Monster. At the Finnish Design Museum it’s Esa. Overall, Scandinavian museums are very focused on families with children, a fact which reflects the general state policy of social and educational support for parents and their children.

|

|

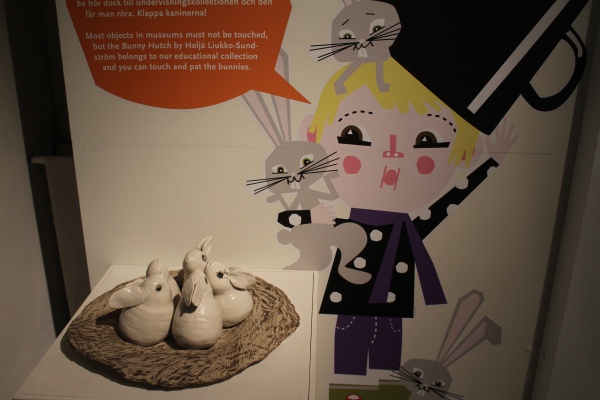

Esa, the mascot of the Finnish Design Museum, explains to children that they are allowed to touch these rabbits in the exhibition. Photo by the author |

The Finnish Design Museum is housed in a beautiful brick building of Neo-Gothic design that housed a school in the past. Perhaps, that is why everything here is steeped in the spirit of education.

The museum boasts of its openness to all segments of the population and offers tours and workshops for schoolchildren, teachers, families with children, students, pensioners and employees of various institutions. This work concept was adopted in the 1990s, explains Paivi Balomenos, head of PR and communication at the museum.

At the same time, it is clear from the programmes offered by the museum that its main focus is the school (students and teachers). Since “providing services to them is one of our core functions as a museum funded by the public,” Piavi Balomenos adds.

Workshops and tours are on offer for school and preschool children; while for teachers, educational materials and the possibility to rent certain facilities for free to hold lessons.

The development of digital technologies has expanded work possibilities. Thus, in the early 2000s, the first educational materials and documented exhibitions appeared online.

“We did not conduct special studies into the need to develop this area,” says Paivi Balomenos. “Many of them arose in the process of collaboration with teachers and educators.”

|

|

A studio at the Finnish Design Museum where workshops for schoolchildren are held. Author’s photo |

Now contact with the audience is carried out actively via the website, which also offers a digitised museum collection.

Conclusions can be drawn about the hospitability of a museum from such basic services as the availability of buggies and wheelchairs, the possibility to bring snacks and lunches (there’s a special place for this) as well as taking photographs of exhibits.

STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN

In autumn 2015, the Swedish government announced the introduction of free admission to some state museums as “equal access to our shared cultural heritage should be seen as a democratic right and that it is important for as many people as possible to feel that museums are there for them”.

The Minister for Culture and Democracy Alice Bah Kuhnke personally stated: “Thanks to free admission, it will be easier for new groups to visit museums.”

Obviously, the issues in question here are the usual high prices for admission tickets (according to the standards of Scandinavian countries) and the need to integrate migrants into the national cultural space. The sum of 80 million Swedish krona (about 8.63 m euros) were earmarked for this.

Such a programme was introduced in 2005-2006 for the first time. At the time, the number of visitors increased significantly due to free admission to 19 main museums. As soon as the programme was over, the flux of visitors decreased.

According to the data of the Swedish Agency for Cultural Policy Analysis, exhibitions and tours remain the most common activities in Swedish museums.

Interestingly, according to the latest survey taken in 2014, the largest number of lectures, seminars and debates were held in regional museums. Regional and municipal museums often offer a variety of cultural events and walking tours too.

The agency also notes that one of the current ways for attracting visitors is being active on the Internet, particularly on social media. Thus, many museums are working on digitising their collections and presenting them on their webpages. However, data on the number of such institutions is not currently available.

Research for 2012 revealed that Swedish museums offer most of their activities to children and young people. More than half of the museums (mainly central museums) have programmes for children and young people with special needs.

One of them is the Swedish Museum of Natural History. Over half of its visitors are children, young people and school groups. The museum says that “such visits are important for fostering interest in nature, its diversity and efforts to preserve it.”

|

|

The Swedish Museum of Natural History holds over 9 million exhibits from all over the planet. Photo: United14 |

Education and accessibility prevail here. Starting with free entry and ending with qualified staff: biologists, geologists and teachers. Apart from the usual function of setting up exhibitions, they also prepare educational materials (which can be downloaded from the website, and some are even available in English), give guided tours and are in charge of a children’s club.

There is also the IMAX Cosmonova theatre, where you can watch educational films on a dome-shaped screen.

Thus, “the museum increases pupil’s thirst for knowledge”. Interestingly, you are allowed to bring your own food to the museum: you can have a snack in specially designated areas for picnics.

One of the capital’s most popular museums is the Nordic Museum, which presents the culture and life of the region from the 17th century to the present. The sumptuous Renaissance Revival building has stairs, so a lift was installed in the side entrance for visitors in wheelchairs or with buggies. There is also the possibility to rent a buggy or wheelchair at the museum.

The Nordic Museum offers tours and programmes for different segments of the population. They include participation in the free “Swedish for Immigrants” national language course.

|

|

You can rent wheelchairs for people with special needs and use a special lift at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm. Photo: Jim_Filim/Depositphotos |

The theme of immigration and cultural diversity gained relevance in Sweden in the 1970s: refugees from former Yugoslavia, Middle Eastern countries and Latin America began arriving at that time.

This challenge became particularly prominent in the 2000s when the number of migrants reached a peak for the first time in the history of migration recordkeeping. The Nordic Museum offers teachers of such courses the opportunity to book a tour for their students (both schoolchildren and adults).

The educational component is one of the museum’s main areas of work. “The Nordic Museum offers tours and programs for pupils and students at all education levels. We organise them to order,” explains Wenke Rundberg, head of the pedagogy and education department.

Adults (high school students fall under this category here) learn about history and life through the “Table settings”, “Interiors”, “Folk art”, “Power of Fashion”, “Textile Gallery” programmes. A Playhouse especially for children has been created.

|

|

The Nordic Museum offers educational tours and excursions for schoolchildren. Photo: jeff-davidson.blogspot.com |

The Nordic Museum’s programmes are adapted for visitors with special needs. For example, there are human models in different historical costumes available to touch at the “Power of fashion” exhibition (the audio guide provides a description).

Every year the museum organises public tours for visually-impaired people. The Playhouse is also available for children with special needs.

TALLINN, ESTONIA

Two establishments that are part of the network of the Art Museum of Estonia are the most productive in the field of offering services. They are the contemporary KUMU (Estonian art from the 18th century onwards) and the Baroque Kadriorg Palace (Western and Russian art of the 16th-20th centuries).

The KUMU building was unveiled in 2006, and in just two years it received the European Museum of the Year award.

“This is a noteworthy international recognition of Kumu’s aspiration to become a truly contemporary art museum, which is not just dedicated to collection, conservation and exhibition, but is a multifunctional space for active mental activity, from educational programmes for small children to discussions about the nature and meaning of art in the modern world,” says KUMU.

|

|

The building of the national Estonian Art Museum. Photo: jaime.silva/Flickr.com |

Equal and full access to the museum is provided both physically and virtually: the building was built to meet the needs of people with reduced mobility, whereas the website provides comprehensive information in four languages (Estonian, English, Russian and Finnish) as well as the ability to take a virtual tour.

Go to the “Learn and Explore” section. Here you will find over 20 programmes for visitors from 2 to 60+ years old: tours, workshops, educational programmes and studios.

A lot of attention is given to the study of the Estonian language for the Russian community, which is also reflected in the content of the website: some information about the educational programmes is more exhaustively presented in Russian than, let’s say, English.

In the digitised archive on the website you can view artwork from the collections of the Art Museum of Estonia.

This year KUMU will, for the second time, open the film festival whose focus is on “the relationship between film and the visual arts”.

The Palace School is in charge of the educational programme at Kadriorg. The museum’s employees are aware that “in comparison with conventional guided tours, the museum’s activities offer more opportunities for reflection, independent discoveries and expressing one’s opinion”, so the main focus is on the preschool and school age audiences (within the framework of the museum’s educational programme).

|

|

At Kadriorg, the Palace School offers visitors a variety of art workshops and lectures. Photo: kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee |

One of the most original projects at Kadriorg is the museum of yoga, classes on physical education and the arts.

The museum does not shy away from the adult public: besides the usual lectures, the museum, for example, offers musical evenings. And disabled people from various age groups are no exception.

***

It is hard not to notice the fact that today museums are fighting for their visitors, feeling the heat of competition not only among themselves but also with other modern ways of acquiring new experience and information – ranging from the media to various cultural centres.

The list of the main functions of a modern museum, besides “preserve” and “process”, now includes “share” (with as wide an audience as possible).

Each of the museums mentioned here represents a unique national theme – art, design, nature, traditions – and tries to talk about it in the most interesting and fun way not only to their diverse compatriots, including immigrants, but also tourists.

And the fact that, for example, Finnish museums include in their audience people with “special needs” is a powerful sign of a civilised country in the 21st century.

Two years ago I discovered to my surprise that I belong to this group: the wheels of a baby buggy don’t go well with stairs and other obstacles on the road, and a loud child is not an ideal museum visitor.

But not in Finland, because for 6 months now my friend and her boy and I with my son are permanent guests of numerous Finnish museums: children attend workshops and have the possibility of touching certain exhibits and learning about the history and culture of this country.

And though children running through halls does somewhat annoy the supervisors, be that as it may, they still ask us back with a smile.

The text was prepared by Ukrainska Pravda with the assistance of the EU-EaP Culture and Creativity Programme.