When LOVE takes over: how Robert Indiana's artwork conquered the planet

When Pope Francis came to the US recently, he was greeted by a very American artwork. On the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, just behind the platform where the pontiff held an outdoor mass, was a monumental red and blue sculpture – four letters, stacked two by two, to read AMOR. It’s a Spanish-language variant of an artwork so ubiquitous that it’s exceeded its artist’s career, and indeed the boundaries of art itself.

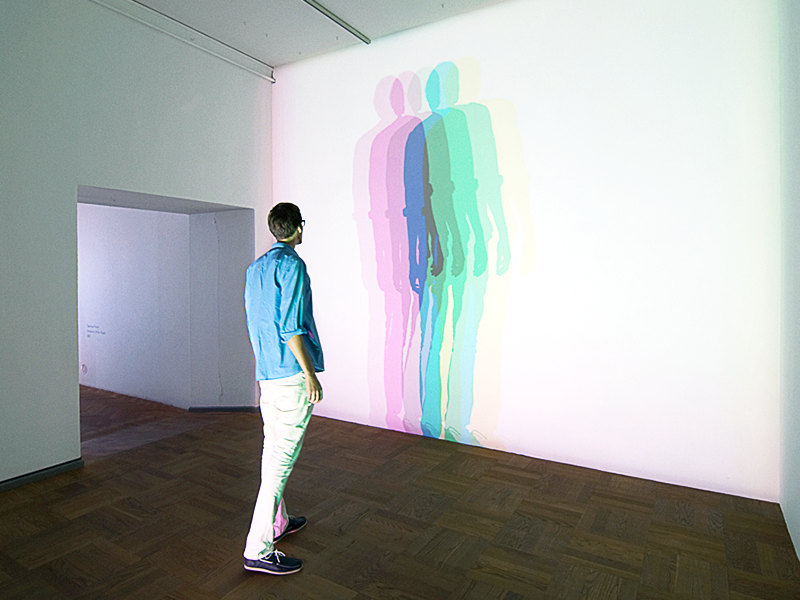

“I just find it fascinating that it’s travelled so far,” says Robert Indiana. The American pop artist, who’s now 88, is sitting in his island home off the coast of New England, reflecting on his 60-year long career ahead of his first British exhibition in a decade. His work LOVE, with its four letters stacked in a square and its O at a jaunty angle, is so famous that many millions of viewers may not even realise it’s an artwork at all. But it is an artwork – one that hovers over Indiana’s career like a helicopter, and that has obscured almost all his other work over the past six decades.

It was MoMA, too, that asked him to design a Christmas card in 1965, an invitation he happily accepted. He thought of the posters he saw at the Christian Science churches he attended in his youth: God is love, they read. He painted the four letters of that mighty word in a bold typeface and a wild colour scheme, in which red and blue and green jostled against one another. It was of a piece with his other works ... but it took on a life of its own.

LOVE proliferated, from 1966 onward, in both authorised and unauthorised forms: as cufflinks, on skateboards, as a Google doodle. Indiana failed to copyright it, as he was wary of adulterating his artwork with a signature – so while his artwork became as famous as the Mona Lisa, the man himself did not. Postage stamps emblazoned with Indiana’s LOVE sold in their hundreds of millions. LOVE sculptures dot the streets from New York to Taipei. But it was always more subversive than its commercial plagiarists understood. LOVE had countercultural implications as America intensified its campaign in Vietnam: for many in the antiwar movement, love and peace were interchangeable – and its universal invocation had particular resonance coming from a gay man in the years before Stonewall. LOVE was no easy hippie affirmation, but an ambiguous artwork no less politically engaged than Indiana’s civil rights paintings.

More: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/oct/09/robert-indiana-love-artwork-sculpture