From Idea to Implementation: Urban Creativity in Small Cities in Well-Defined Steps

Monica Babuc, the Minister of Culture, mentioned during the opening of the event that `urban development and the concept of creative cities are important for the economy of a country’. Ragnar Siil, expert of the EU-Eastern Partnership Culture and Creativity Programme, added that ‘one euro invested in a festival brings four euros to the community budget’. Pirkka Tapiola, the EU Ambassador to the Republic of Moldova, highlighted that ‘now it is important to build a city where people want to live’.

The participants in the event had the opportunity to grasp the meaning of ‘creative cities’ and ‘urban development’ on the basis of concrete examples of European cities. They also learned how to budget correctly a project idea related to creative development of a big or small city, and how to find the creative potential of the cities.

Not only big cities have opportunities – Creative things of small towns

The British expert Lia Ghilardi said that: ‘The future belongs to small towns. Here, young people can strengthen their energy and creativity. This is determined by the times we live in, and namely by the fact that about 50 thousand empty apartments are currently found in the center of London. They are bought as money ‘recycling tool’. What does this phenomenon mean for the creative people who come to study or work in London? They cannot rent a living space. In most of cases, the creative ones are the youth, i.e. university graduates who return to their homes’. The expert emphasized that `smaller towns are more agile and flexible as regards the urban creative development. In small towns, people know each other, they are more receptive and communicative. This is why small communities have more opportunities’, she concluded.

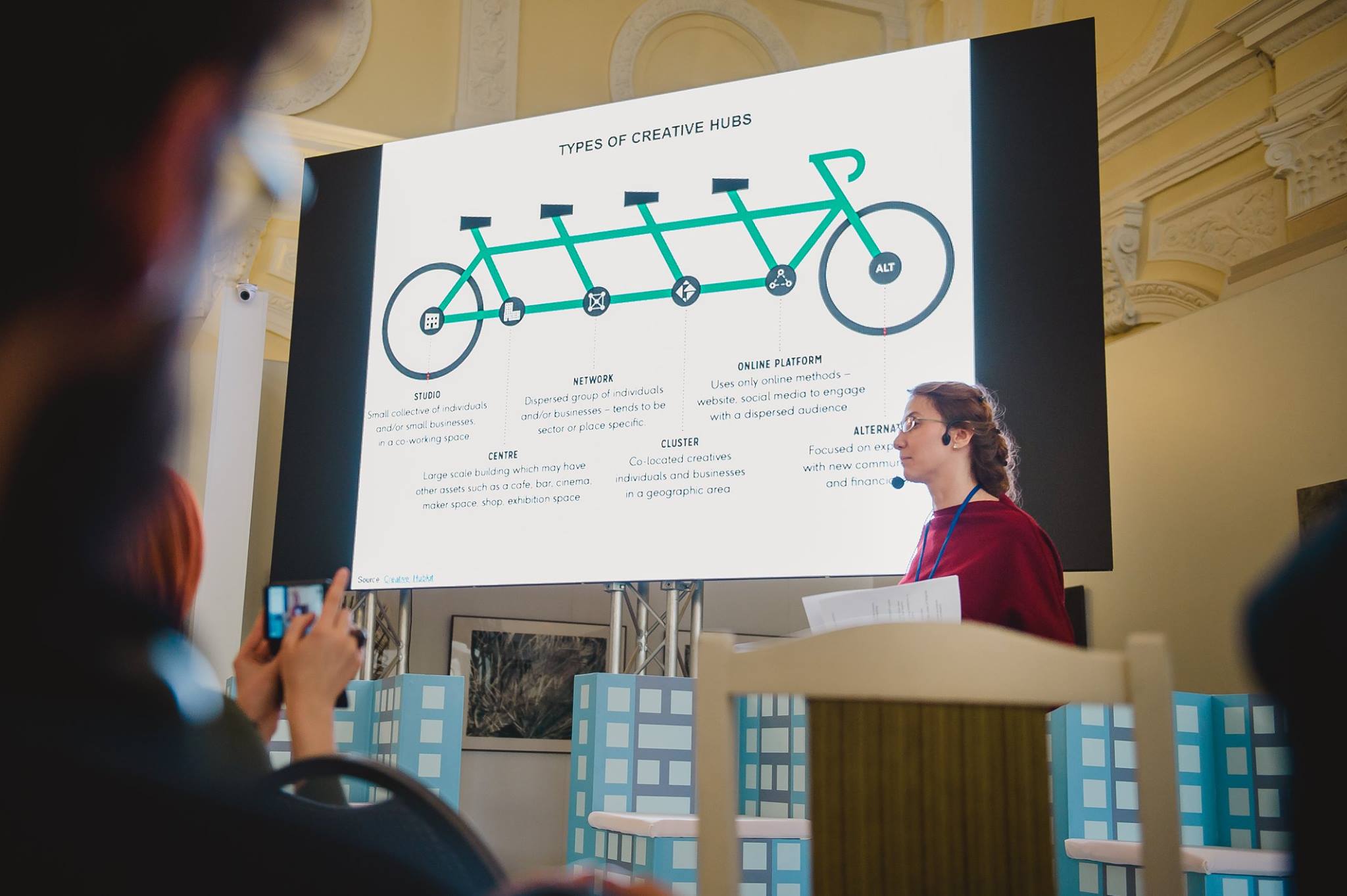

Experts’ speech session continued with Philippe Kern, an international expert of KEA European Affairs, who stated in his presentation ‘How to invest wisely into culture and creativity?’ that: ‘Politicians believe that innovations come from the technology sector. It is important for politicians to understand the role of the creative industry for the economy and other areas.’ He also believes that ‘culture and creativity attract investments, and that the towns (hubs, incubators, etc.), not the ministries of culture, are the driving force of investments in culture. In the end, he mentioned that `one euro invested by the authorities in the creative industry generates five euros for the Belgian economy’.

The expert Reigo Kuivjõgi gave an example of supporting creative entrepreneurship in small and medium-sized towns, based on the example of Tartu, Estonia. 10 years ago the young graduates from the universities in Tartu – recognized as students town, with a population of about 100,000 inhabitants, and young people aged 18-24 as target segment, used to emigrate. Thus, the creative idea and decision to keep the young people at home or in the city focused on developing the creative industry – creating business incubators.

Simon Williams, director of British Council Ukraine, pointed out that: ‘Creative businesses (creative entrepreneurs) are bridges between authorities and the creative ideas of the society.’

The vocalist of the Gandul Matei band, Nicu Tarna, concluded the first day of the Forum with a quotation: ‘The history of a state is painted on the old buildings’. He presented the idea to restore the building of Chisinau circus and to organise an event named ‘Lumineaza circul’ (Light Up the Circus) on 5 May, aiming to use the renovated circus for cultural events.

The participants concluded at the end of the day that the creativity of a city means a city where people want to live and to create. They also developed a theoretical action plan for the creative initiatives of the Republic of Moldova.