Sofia Sadovskaya: “If Parents Don’t Like Contemporary Art, This Doesn’t Mean That Their Children Don’t Like It”

There is a widespread belief that children can be taught to draw, sculpt, etc. But can children be taught art?

For this, we have to understand what art is. Art is not a set of facts, stories, paintings. Art gives people the opportunity to go through a certain experience. Experience is not simply information and answers to questions “What year was the work painted?” and “Who’s the artist?” The idea of our workshops was to create a situation where children could receive different experience from interacting with art.

What are the ages of the children you work with? How are the classes structured?

We understood that kids under six just need to draw, with an informational load. Therefore, we refused to work with little children and left out primary school children. Participants of our project are children aged between seven and 12. We would like to have started working with teenagers, but we still didn’t have such experience. These are group classes of 15 persons that are one and a half hours long. They are divided into three main parts:

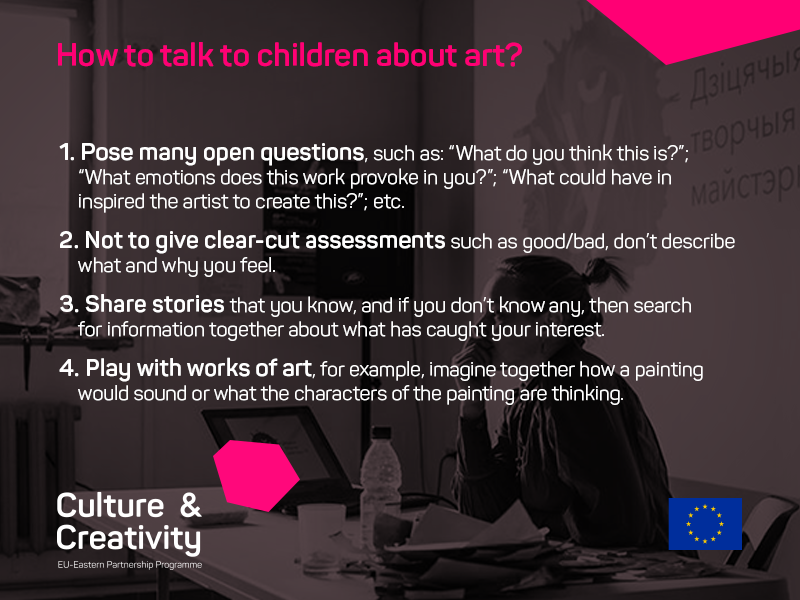

1. A discussion with open-ended questions: You can’t answer with a “yes” or “no” open-ended questions. We don’t ask children who painted the picture and when. We ask them “What do you see?”, “What do you feel?” I have a favourite question: “What do you think inspired the artist to create this work? Of course, we can’t know for sure what the artist was feeling, but we can imagine. Answers help to find connection with the work and deepen our understanding of the work of art, both for adults and children. The discussion lasts 10 to 15 minutes. I, of course, talk about who, when, at what time the work was created, but I don’t check whether the kids remember that. However, in my experience, children remember even facts very well. Then there’s a game.

2. Games: Short games engage children in the creative process. For example, if we’re working on Henri Matisse’s cut-outs. I would project one of his works on the wall and ask the children to imagine that Matisse had invited them to his house and asked them to help him finish this cut-out. This is not an individual game, but a collective work, involvement. Such a form of work helps children by analysing (without actually saying it) an artwork to understand what forms and colours the artist used. We do such exercises in every class.

3. Workshop: This is the main part of the class and it takes around an hour. The workshop has to do with what we’ve already seen and analysed during the discussion and the game. If it’s a Matisse cut-out, then we use his technique. As you know, he didn’t use to buy colour paper, but coloured white paper himself. This means that children have to colour several pieces of watercolour paper, they learn to mix colours and create a cut-out. This is an hour of their personal work. Another example is the artist Alexander Colder, who came up with mobiles, a type of suspended sculpture, and created sculptures from wire. When we studied his work, we showed the children works by the sculptor and proposed that they create their own mobiles, or sculptures from wire and paper. Each one created something of their own.

How do you choose artists for the classes? Are there any Belarusians among them?

Yes, we did examine the work of several Belarusian artists, but it doesn’t happen often. However, this season begins with a cycle of classes completely devoted to the artists of the Vitebsk School.

Our classes are held in a contemporary art gallery. Therefore, we can devote classes to works and artists exhibited at the gallery. For example, at Y Gallery there was an exhibition by Ukrainian-German artist Aljoscha who brought unusual biomorphic installations to Minsk. We examined these installations, then the children wrote poems about them, danced around these installations and created their own objects with similar materials.

What engages children most of the above-mentioned activities?

All the components of the class have a complex effect. Almost any artist can be presented in a way to be interesting to a child. Children are fascinated by art. For example, kids like les Fauves – bright colours, clear forms, as well as the work of Marc Chagall – it is fabulous and there is a lot of magic in his works. Older children love realism, especially at that time when they’re learning to draw themselves. All children go through the stage: “Wow, it’s drawn just like in a photo.”

We don’t present information in the form “this is good, and this is bad”. We show that art can be very different. Our main goal is to teach children to be open to different art.

What areas of contemporary art are presented to children? Visual, performance, literature, music? Are there genres that are more suitable for children, and what interests them least?

We study all forms of contemporary visual art. To a lesser degree, performance, more installation, site-specific works, sculpture, painting, sometimes music. For example, Kandinsky often linked his works with experimental music composition and when we worked on Kandinsky we listened to that kind of music.

How do you explain to children what “installation” is?

This is an object in space, more complex than a sculpture, a composite created from various elements. Installations can include video, sounds, and other additional items. Installations can be shown on the street, and other unexpected places for classical art, with the use of unorthodox forms and materials.

What can be considered the result of such classes? How can you “measure” the success of the educational process?

This is quite a difficult question. Today’s parents like the answer to the question “What did the child learn?” to be specific. I myself would be very interested in finding this answer.

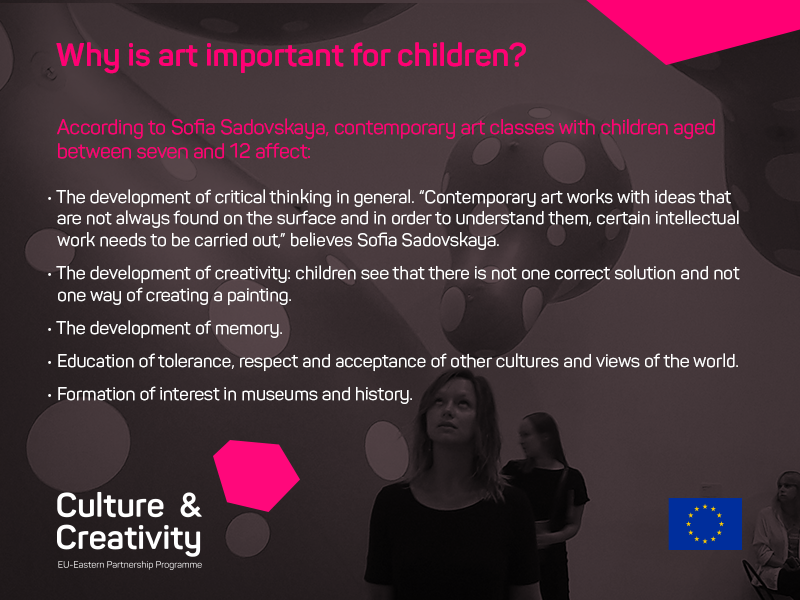

There are scientific studies that show that children who go to museums and attend other cultural establishments have better developed memories, they tend to have a better understanding of historical events, they have deeper historical empathy, and empathy in general – feeling the world, they perceive various forms of art more easily and use critical thinking. This means that analysing artworks has a great impact on the ability to reason.

The main goal of my work is developing interest for contemporary art, forming critical thinking, the skill of analysing. Of course, context is important too, and children gradually learn about it in the course of their learning.

As a consequence of the classes, there is the formation of a certain culture of reasoning, which children can subsequently apply to a book they read or a picture they see. We want the child to understand what are the questions to ask oneself to analyse any artwork and draw one’s own conclusions. This is our goal.

Do children change over the course of the classes?

Sometimes, at the beginning of the classes, when I show some unusual work and ask “What do you think this is? Is this art?” children respond “no” or “probably not”. But gradually, their answer changes to “maybe”, “possibly, this means…”, etc. Children who attend classes all the time don’t even wait for the question. I show a projection of an artist’s work and they immediately begin to discuss “I believe that the artist was inspired by…” They don’t have rejection, fear, they’re not afraid. And this is my success. For fear gives rise to misunderstanding, hinders the ability to reason.

What part do adults play in the learning process?

I believe that adults should not interfere in the process of the workshop and child’s work. But when adults participate in the discussion process, that’s good because we all have different views. Frankly speaking, however, parents don’t often stay for the class. We held special lectures for parents to explain to them what happens during classes.

If parents don’t like contemporary art, this does not mean that their children won’t like it. You shouldn’t tell a child “This is incomprehensible”, “I don’t like it”, etc. It’s better to ask them “What do you think about this?” without giving your assessment. Children can give very interesting comments on works and reveal them in a completely unexpected aspect. It is often difficult for adults to accept things they don’t understand. Children don’t have a cultural background, that of an adult, they don’t have fear, and that is why they can themselves begin to love and understand contemporary art.

Possessing experience in this sphere, could you name the mistakes, misconceptions that exist with regard to teaching children contemporary art? How to avoid and not repeat them?

Well, there’s a view (mistaken in my opinion) that small children shouldn’t be shown art of the 20th and 21st centuries. I believe this is a misconception. Children are very open to various forms of art, and I don’t think that there should be any limitations.

We made some mistakes in the course of our work. At one point we understood that we were devoting classes to very famous artists only: Matisse, Chagall, Van Gogh. And we get large groups for these – parents are familiar with these names. But we wanted to go further, and when we added names of not-so-popular artists to the programme, in addition to world famous artists, namely Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama or sculptor Anish Kapoor (UK/India), five people came to the class… Adults don’t know and don’t understand them, why take a child to a class with an obscure theme. That is why we decided that we had to change the way we presented information for parents. Now we don’t give the name of the artist, only the theme of the class.

Children always know what’s represented in abstract paintings. They have a unique answer, their own interpretation.

How to expand the practice of teaching children contemporary art? What are your plans?

I believe that it is very important to work with educators, museum employees, so that they understand why one should take children to contemporary art museums. We are currently preparing a book about Belarusian 20th century art for children. This will be the first such publication in our country. The art of the 20th and 21st centuries remain beyond the framework of school curricula. I would really like to create my own studio as classes in a gallery have their own issues. We would like to give children more freedom.